Engaging With Others Not Yet on an Expedition with Christ

I Peter 2:9-12, 15-16

The Apostle Paul says that Christians are called to live with their feet firmly planted in two different worlds. He says we’re a chosen people, a royal priesthood, God’s special possession. We’re bound for the glorious Kingdom of God. Then Paul talks about how we’re foreigners and exiles. We reside on earth, but our citizenship is in heaven. There’s a well-known phrase for people who find themselves in this unique situation: they’re called Resident Aliens. In legal terms that’s someone who’s a permanent resident of the country where they live, but they don’t have citizenship. That is what Paul was reminding the church about: they symbolically have a foot in two places, earth and heaven. Each is distinct, but since they belong in both, sometimes there’s a shared overlap.

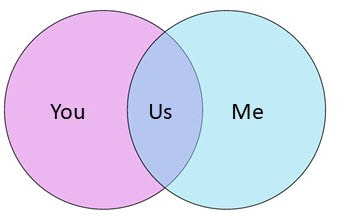

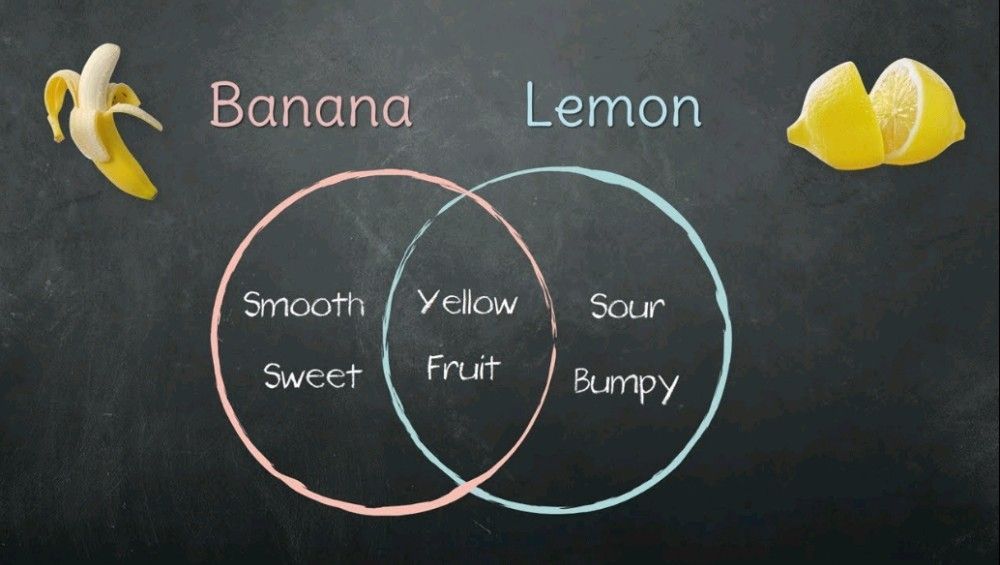

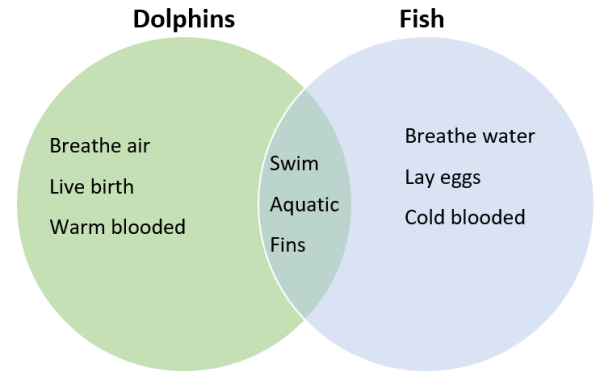

A great way to see this come to life is to use a Venn diagram. Here is a starter example: two separate circles, one labeled “me” and the other “you”. Each is unique and separate, but sometimes “me and you” come together as “us”. Do you still remain fully you? And do I remain fully me? Absolutely. There’s a name for this “almond shape” in the middle. The place where there’s an overlap is called a mandolin – it’s where we have something in common (here are some other examples of Venn diagrams).

A great way to see this come to life is to use a Venn diagram. Here is a starter example: two separate circles, one labeled “me” and the other “you”. Each is unique and separate, but sometimes “me and you” come together as “us”. Do you still remain fully you? And do I remain fully me? Absolutely. There’s a name for this “almond shape” in the middle. The place where there’s an overlap is called a mandolin – it’s where we have something in common (here are some other examples of Venn diagrams).

There can also be more circles, each one overlapping with one or more others. There’s a reason why I’m explaining the basics of Venn diagrams: this morning begins a three-week preaching series based on J. R. Briggs’ 2020 book called, “The Sacred Overlap: Learning to Live Faithfully in the Space Between”.

The best way I know to give you an overview of this book is to share what was written by Tod Bolsinger, author of “Canoeing the Mountains”:

The best way I know to give you an overview of this book is to share what was written by Tod Bolsinger, author of “Canoeing the Mountains”:

In a day where the world, our culture, and the church are marked by a continual default to division and defensiveness, J. D. Briggs offers us a vision of an interconnected, integrated, and incarnated way of being in the world. In the engaging and entertaining ‘both/and’ character of this book, Briggs helps us to see God and reality in ways that are both deeply inspiring and profoundly uncomfortable, completely biblical and distressingly destructive, breathtakingly spiritual and shockingly down-to-earth. This book should be read by people who want to be formed into someone who can personally participate in crossing divides and working for a genuinely restorative common good and are willing to have their assumptions challenged every step of the way.

Let’s delve in! Today’s Venn diagram, which I’ll call a Sacred Overlap from now on, is based on Paul’s message and looks like this: inhabitant is one circle, foreigner is another circle, and they are overlapped. The first-century Christians who heard Paul’s letter read to them had no familiarity with Venn diagrams, or sacred overlaps, but they were very familiar with the dynamics at work.

Every year on Passover they celebrated the exodus of their people from slavery in Egypt. Their ancestors spent forty years in the desert wilderness as a free people, but they hadn’t yet reached the Promised Land. Once they settled, God told them to build homes and plant gardens, to live as people of peace, of shalom, with their neighbors.

God then described the sacred overlap He expected of them. Israel was to be a holy nation, it’s people willingly following the teachings of God. However, there were villages of people surrounding them, a day’s walk away or less, who were ignorant about God. They had little concern for right or wrong, so people did whatever pleased them.

God wanted his people to live their lives as usual, with their faith out in the open. If they happened to see their unbelieving (pagan) neighbors, they shouldn’t avoid interacting with them, nor should they silently judge or shun them. They also weren’t allowed to retreat and live in isolation. Those extremes are off the table. God is interested in His people living a mandolin life of faith, living in a sacred overlap, living as resident aliens.

Paul’s audience knows this history; they realize that as Christians they must engage with the world but be careful so they aren’t corrupted by it. That isn’t easy to do; there are always enticing temptations that seem harmless but can lure us, step by quiet step, away from holy obedience to God. You and I know that sin will take us farther away from God than we ever planned, and sin can keep us there longer than we ever imagined.

God wants us to learn to navigate the tensions that come with living as faithful Christians in an unbelieving and sometimes hostile culture. We have an outstanding example of how to do this, thanks to an inspiring young man called Daniel. He and two other faith-filled friends became slaves when the Babylonian armies conquered Israel. They were living on foreign soil, in a pagan culture, but they didn’t compromise their faith. They lived a mandolin life, finding ways to navigate the tension.

I hope you’ll read the book of Daniel for yourselves this week. Daniel and his friends were assigned to work at the king’s palace. They were given new names and had to master a new language. They were taught new customs and served new kinds of food. Despite this disorienting immersion, they did their jobs with excellence, and followed every rule that didn’t conflict with their faith. But people who were jealous of their success persuaded the king to decree that for 30 days, no one could pray to anyone but the king. Of course, Daniel would never consider NOT praying to God, so there was an interrogation. Daniel’s response was courageous, but respectful, as he explained how he remained committed to his holy God and was also an obedient slave to the king.

Daniel suffered consequences for practicing his faith: he was thrown into the lions’ den. But even before God rescued him from the mouth of the lion, Daniel maintained his trust in God and faithfully navigated the tension between his faith convictions and the Babylonian way of life. In the words of author J.R. Briggs, Daniel had confident tranquility.

I love that expression – it’s stayed with me all week. Someone else who comes to mind when I hear those descriptive words is Jesus, our Lord. I think his disciples would’ve said he embodied “confident tranquility”. They watched the Son of God approach sinners and scoffers with genuine interest. He talked with testy Roman governors and spent time at midnight with people who were too scared to see him in the daytime. They came with questions, worries, and needs. With confident tranquility Jesus spoke with all sorts of people who weren’t yet on an expedition of faith. In those conversations there’s a sacred overlap, when people’s hearts may be open to the in-breaking of God, new ideas, and exploring a life of faith. That’s the advent of the Kingdom of God.

If a poll was taken and Christians were asked how they felt about having a one-on-one conversation with a non-Christian about faith, a sacred overlap conversation, how many people would feel confident tranquility? And what percentage would feel anxiously insecure? Next week, I promise to share three simple guaranteed ways we can start a conversation with anyone that can lead to God and faith.

Meanwhile, I want to leave us all emboldened by J. R. Briggs’ humorously accurate description of how Jesus lived in the world, but He wasn’t of it:

Every year on Passover they celebrated the exodus of their people from slavery in Egypt. Their ancestors spent forty years in the desert wilderness as a free people, but they hadn’t yet reached the Promised Land. Once they settled, God told them to build homes and plant gardens, to live as people of peace, of shalom, with their neighbors.

God then described the sacred overlap He expected of them. Israel was to be a holy nation, it’s people willingly following the teachings of God. However, there were villages of people surrounding them, a day’s walk away or less, who were ignorant about God. They had little concern for right or wrong, so people did whatever pleased them.

God wanted his people to live their lives as usual, with their faith out in the open. If they happened to see their unbelieving (pagan) neighbors, they shouldn’t avoid interacting with them, nor should they silently judge or shun them. They also weren’t allowed to retreat and live in isolation. Those extremes are off the table. God is interested in His people living a mandolin life of faith, living in a sacred overlap, living as resident aliens.

Paul’s audience knows this history; they realize that as Christians they must engage with the world but be careful so they aren’t corrupted by it. That isn’t easy to do; there are always enticing temptations that seem harmless but can lure us, step by quiet step, away from holy obedience to God. You and I know that sin will take us farther away from God than we ever planned, and sin can keep us there longer than we ever imagined.

God wants us to learn to navigate the tensions that come with living as faithful Christians in an unbelieving and sometimes hostile culture. We have an outstanding example of how to do this, thanks to an inspiring young man called Daniel. He and two other faith-filled friends became slaves when the Babylonian armies conquered Israel. They were living on foreign soil, in a pagan culture, but they didn’t compromise their faith. They lived a mandolin life, finding ways to navigate the tension.

I hope you’ll read the book of Daniel for yourselves this week. Daniel and his friends were assigned to work at the king’s palace. They were given new names and had to master a new language. They were taught new customs and served new kinds of food. Despite this disorienting immersion, they did their jobs with excellence, and followed every rule that didn’t conflict with their faith. But people who were jealous of their success persuaded the king to decree that for 30 days, no one could pray to anyone but the king. Of course, Daniel would never consider NOT praying to God, so there was an interrogation. Daniel’s response was courageous, but respectful, as he explained how he remained committed to his holy God and was also an obedient slave to the king.

Daniel suffered consequences for practicing his faith: he was thrown into the lions’ den. But even before God rescued him from the mouth of the lion, Daniel maintained his trust in God and faithfully navigated the tension between his faith convictions and the Babylonian way of life. In the words of author J.R. Briggs, Daniel had confident tranquility.

I love that expression – it’s stayed with me all week. Someone else who comes to mind when I hear those descriptive words is Jesus, our Lord. I think his disciples would’ve said he embodied “confident tranquility”. They watched the Son of God approach sinners and scoffers with genuine interest. He talked with testy Roman governors and spent time at midnight with people who were too scared to see him in the daytime. They came with questions, worries, and needs. With confident tranquility Jesus spoke with all sorts of people who weren’t yet on an expedition of faith. In those conversations there’s a sacred overlap, when people’s hearts may be open to the in-breaking of God, new ideas, and exploring a life of faith. That’s the advent of the Kingdom of God.

If a poll was taken and Christians were asked how they felt about having a one-on-one conversation with a non-Christian about faith, a sacred overlap conversation, how many people would feel confident tranquility? And what percentage would feel anxiously insecure? Next week, I promise to share three simple guaranteed ways we can start a conversation with anyone that can lead to God and faith.

Meanwhile, I want to leave us all emboldened by J. R. Briggs’ humorously accurate description of how Jesus lived in the world, but He wasn’t of it:

Jesus was too religious for some, and not religious enough for others. He was a raging non-conformist. No one was able to put him into a box. When people tried to force him into one, he'd ask a deflecting question, tell a provocative story, or commit some social or religious faux pas on purpose, which sent religious leaders hissing. Jesus didn't fit in the pagan world, nor did he ever feel completely comfortable hanging out with the religious leaders of his day. Jesus was a moral square peg in a religious round hole, but the irreligious loved hanging out with Jesus. That is, until he tightened the screws by challenging people to live a different way of life.

Jesus taught and interacted with saints in the synagogues and also clinked glasses with his buddies at the local winery (today, a brewery?). He kept the Torah, and also ripped into the religious leaders. He hobnobbed with the rich and the powerful and also touched lepers and allowed his feet to be anointed by a dishonorable woman. Was Jesus a maddening paradox or a frustratingly confusing contradiction? Or was Jesus a model of faithful overlapped living? Maybe he was all three! Jesus’ perplexing peculiarity was the very thing which made his life so attractive, alluring, and impossible to ignore. At times he was too much of a saint for some, but for others he was too much of a sinner. (p.71-72)

Jesus taught and interacted with saints in the synagogues and also clinked glasses with his buddies at the local winery (today, a brewery?). He kept the Torah, and also ripped into the religious leaders. He hobnobbed with the rich and the powerful and also touched lepers and allowed his feet to be anointed by a dishonorable woman. Was Jesus a maddening paradox or a frustratingly confusing contradiction? Or was Jesus a model of faithful overlapped living? Maybe he was all three! Jesus’ perplexing peculiarity was the very thing which made his life so attractive, alluring, and impossible to ignore. At times he was too much of a saint for some, but for others he was too much of a sinner. (p.71-72)

This week, for a life-application challenge, be aware of your call to live a God-honoring life in a pagan world. Think about the times when you connect with people who aren’t yet on an expedition of faith with Jesus. And remember every day, that you and I are Resident Aliens. We have permanent residency in this world, but it isn’t where we hold our citizenship! Thanks be to God – amen.